After leaving Oirase and Aomori Prefecture behind, we turned our way southwards towards Akita Prefecture. From here on, we were heading inland rather than following the coast. The rain did not stop, and as we crossed through the rural countryside with hardly any buildings around us, the weather began to shift constantly. Rain turned into snow and back into rain as we ascended over mountain passes and crossed wide plains. At some point, we passed through a small village with a few signs of civilization, mostly pachinko parlors, gas stations, and convenience stores. We were mainly following national roads through the mountains, often narrow and winding, climbing several passes where the weather changed quickly.

Many of the buildings we came across looked deserted or run down, showing clear signs of depopulation in the area. Inland Akita feels especially affected by this, as access is limited compared to the eastern part of Tohoku, which is far better connected by the JR network and the Shinkansen.

At one point we barely avoided oncoming traffic when we came dangerously close to a truck on a narrow stretch of road. As we approached our destination, the roads climbed higher and the snowfall grew heavier, and we started to worry whether we might need snow chains after all. We stopped briefly to test traction, but the winter tires held well and gave us enough grip to continue. As it kept snowing and the last light of the day faded, we finally arrived at Goshogake Onsen. With it came the unmistakable smell of sulfur. We arrived in the late afternoon, with temperatures already well below freezing.

When we arrived, four pairs of slippers were already prepared, and the receptionist kindly explained the facilities and offerings of the ryokan. Given the timing and the weather, it felt like we might have been the last guests to arrive that day. The ryokan had one large main bath, a smaller secondary bath, and a natural steam-powered ondol hot stone experience, which we could sign up for and which I would come back to later. This time we had two separate rooms, both very traditional and surprisingly warm, apparently thanks to a heating system that directly uses natural hot spring water.

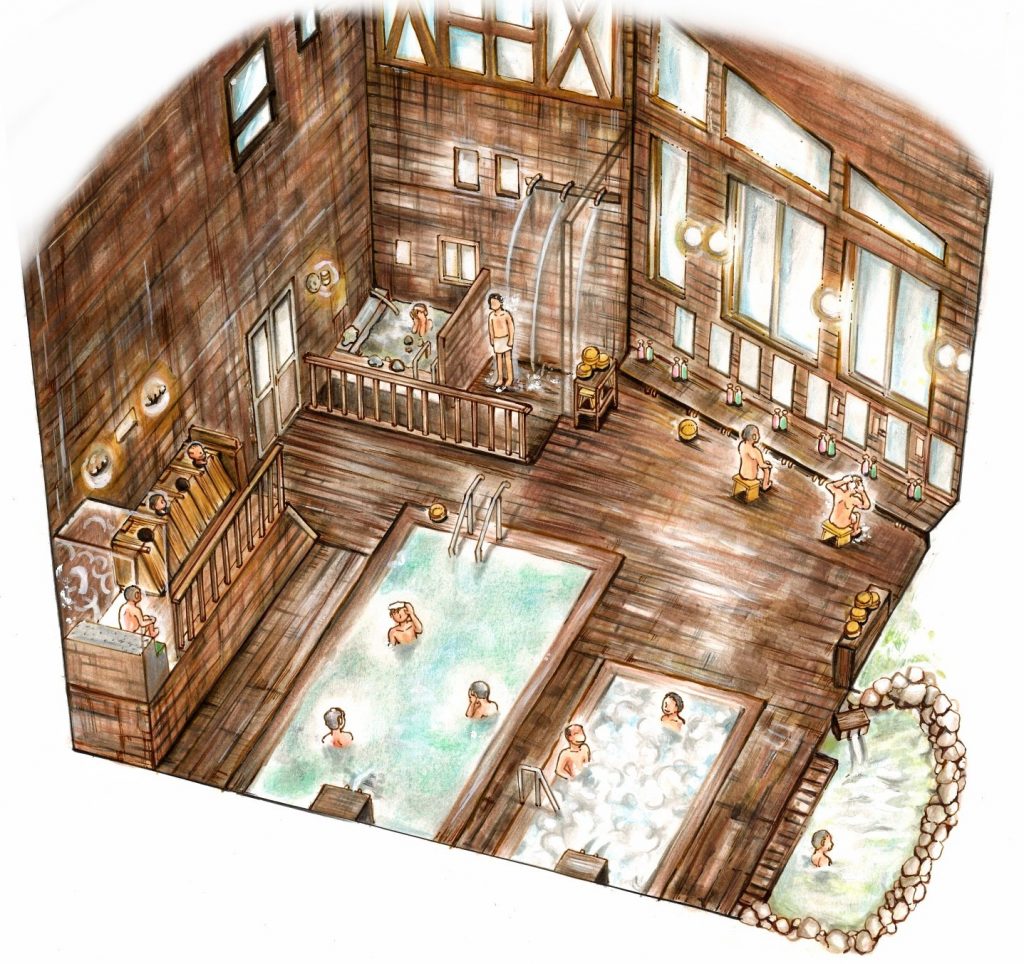

We had enough time to take a soak in the onsen before dinner, and we were immediately impressed by the sheer scale of the bathhouse. When we opened the door, we stepped into a dim wooden space filled with steam, with several pools spread across the room, including a whirlpool, a sauna, and a hot box with a steam outlet where you could enjoy a personal steam session. The large bath contained multiple pools as well as small steam saunas designed for one person at a time. Sitting inside one of these wooden chambers while steam rose from below felt like a quiet, contained way to warm up without fully bathing. The water itself was a milky white color, and the steam was so thick it was visibly foggy. Funnily enough, there were no shower heads, only a water faucet at a bowl, which you used to pour hot or cold water over yourself. After moving between the different pools and spending enough time soaking, it was time for dinner.

As hoped, dinner was an impressive assortment of local dishes. We were served salmon sashimi with fish caviar, several cold dishes made from local mountain vegetables, and two different hot pots, one featuring local Hachimantai pork. There was also a kiritampo hot pot, as well as three thick cuts of wagyu beef. It was served as a long set menu, course after course, and the dishes just kept coming. By the time we reached dessert, we were completely full and could not manage another bite.

Later in the evening, we tried the ondol room. The ondol at Goshogake Onsen is a heated tatami space where geothermal heat slowly rises from below the floor. You lie down fully clothed, wrapped in a robe and towel, and let the warmth spread through your body. The heat is gentle and even, making it easy to stay there for a long time without discomfort. The room was quiet and dimly lit, with no water involved at all, just steady warmth and a faint sulfur smell lingering in the air.

Most guests use it after bathing, before going to sleep. After the baths, it felt like a calm and almost meditative way to let the body fully settle for the night, and it honestly felt comfortable enough that it would have been easy to fall asleep right there on the tatami, if it had not been for a helpful fellow guest whose loud snoring made sure that did not happen. As we lay there, heavy sheets of snow slid off the roof above us, echoing through the building like taiko drums in the darkness.

The next morning, we woke up to find the ryokan deeply buried in snow. I took another quick dip in the bath before breakfast, just enough to warm up for the day. With daylight, the surroundings became much clearer, and we could fully appreciate the mountain setting we were in. It was still snowing lightly, and visibility remained limited. Goshogake Onsen sits at over 1,000 meters above sea level, and every few minutes we could hear snow dropping from the roof outside.

I also visited the second bath, which overnight guests could use freely. This smaller onsen had a window facing the inner courtyard and the same silky, milky water as the main bath. During certain hours, parts of the onsen are also open to day-trip visitors.

Breakfast was served in the same dining area and followed a familiar ryokan style. We had miso soup and rice, a shumai dumpling that we could heat ourselves, onsen tamago, along with pickles and salad.

When we checked out, we asked about sightseeing options in the area, but the receptionist gave a slightly troubled smile and handed us a map showing what was accessible in winter, which was not much. Snow and road closures limit most outdoor activities at this time of year, and many hiking trails and mountain roads were already closed for the season. She mentioned the nearby copper mine museum, which we were planning to visit anyway. Before setting off, we had to clear snow from the car, which turned out to be easier than expected. Once on the road, we were relieved to find that everything had already been cleared.

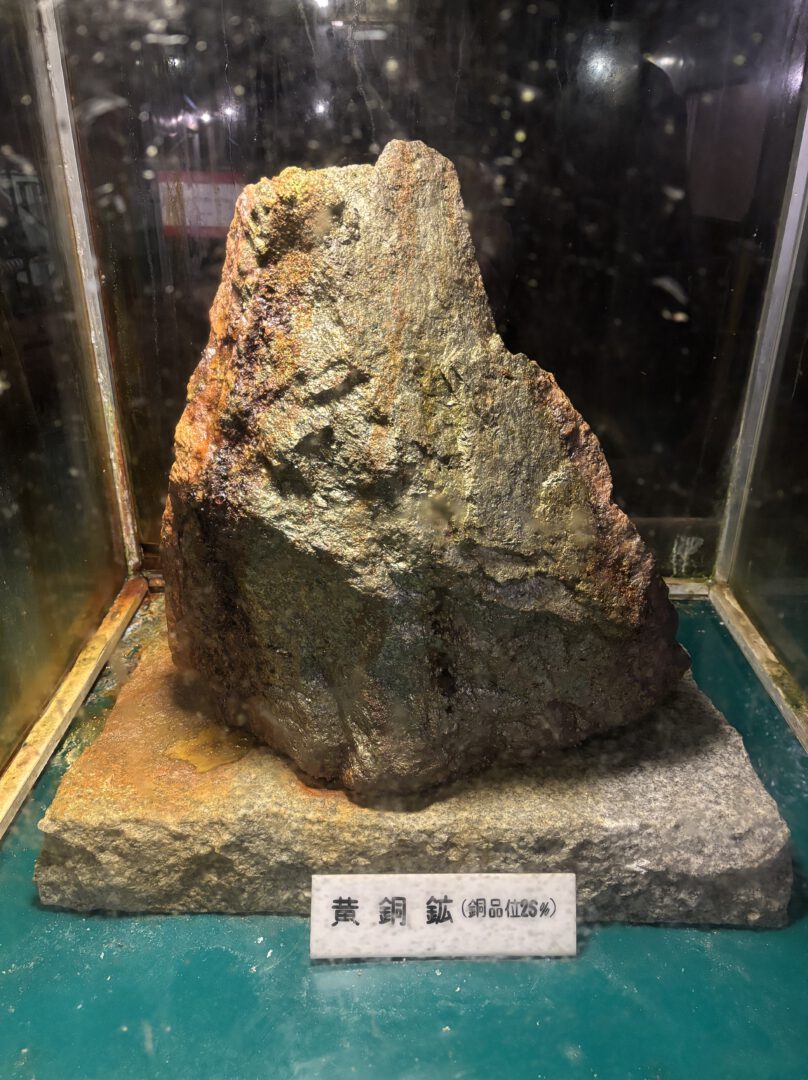

After about half an hour back down the valley, we reached the nearby village of Kazuno and entered the former copper mine museum. This was the Osarizawa Mine, which has a history of over 1,300 years and was once the largest copper mine in Japan.

Mining is no longer active, but the site played an important role in Japan’s metal production for centuries. Roughly 1.7 kilometers of tunnels are open to visitors, and as we walked through them, we passed displays explaining the tools and techniques used in different periods. Over many centuries, miners dug tunnels and shafts across multiple levels, creating a vertical system that reached roughly 450 meters in height, the equivalent of about 15 stories stacked on top of each other, all carved out using simple tools. In some sections, the exposed rock walls are incredibly old, formed millions of years ago, and stepping inside felt like entering a quiet world deep beneath the mountains.

Exhibits recreate mining scenes with mannequins and historical equipment, and information panels explain how mining shifted from gold in earlier periods to copper later on. It is said that gold from this mine was used for the Great Buddha of Todai-ji in Nara and the Golden Hall of Chuson-ji in Iwate, a thought that lingered in the moist, earthy air as we walked through the tunnels. The steady silence and low temperature made it easy to imagine how hard and dangerous this work must have been.

Beyond the tunnels themselves, there were also areas for repairing machines, a cafeteria, and even a shrine once used by the workers. We saw elevators and rail systems that had transported both materials and people. At times, it felt less like a mine and more like an entire underground settlement.

In the Edo period, attempts were initially made to extract gold from these shafts, before mining gradually shifted toward copper due to its greater abundance and value for industrial use.

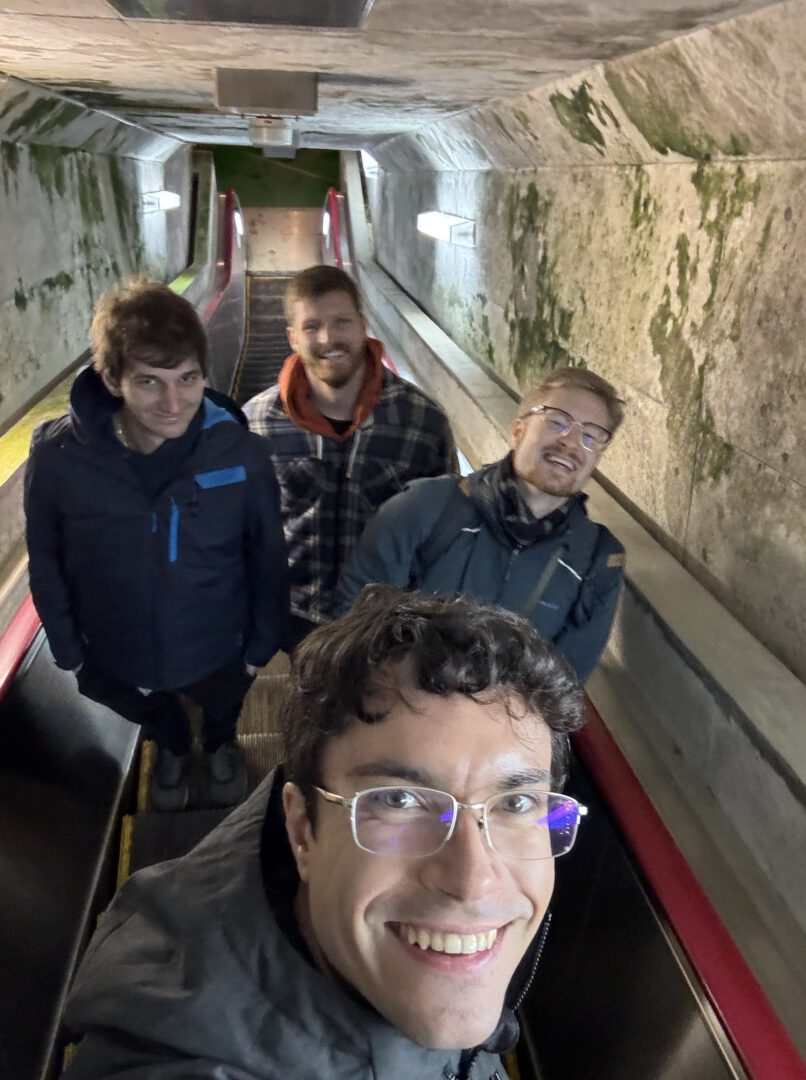

The visit ended with an unexpected modern-day escalator that brought us straight back to the surface, a slightly anti-climactic but memorable way to leave the depths of the mountain. Typical Japan.

We made a short stop at a michi-no-eki rest station, where we admired the impressive size and quantity of local apples. We also bought some Akita Komachi rice and had soba before continuing on. From there, we drove toward Morioka, one of the main cities in the region, which we had already visited once before in January. Morioka was selected as one of the New York Times “52 Places to Go in 2023,” bringing wider attention to the city. It is an easy place to like, often compared to Kanazawa, and I could genuinely imagine living here.

Before heading to the former castle grounds, we stopped at a local kissaten with a cozy interior and excellent coffee, which felt like the perfect break after the long drive. We had arrived right at the peak of koyo season, and the former castle park was filled with deep red maple trees. The trees stood within Iwate Park, the old Morioka Castle ruins. Our time was limited, though, and after a short walk and a visit to a wagashi shop to pick up omiyage for friends and family, we moved on.

From Morioka, we continued east toward Lake Tazawa, where our next stay would be at a ryokan right on the lakeside.

Entdecke mehr von Tabimonogatari - 旅物語

Melde dich für ein Abonnement an, um die neuesten Beiträge per E-Mail zu erhalten.